LatGen. Dor Shabashewitz’s Latvian family history research blog

Sveiki! I’m a Russia-born Israeli from a fairly mixed family with a great deal of Latvian heritage. Both of my mother’s parents have ethnic Latvian ancestry from Vidzeme (Daugavgrīva, Lazdona, Mazsalaca and Piņķi parishes) and Kurzeme (Liepāja), and my father’s earliest known Jewish ancestors lived in Latgale (Bļaši near Kārsava). Since those on my mother’s side were culturally and linguistically Germanized by the early 20th century (more on this later), I didn’t grow up speaking Latvian but I’m trying to make up for this by learning the language as an adult. As you can probably tell, researching my Latvian lines has always felt especially fascinating. I’ve spent enough time doing this to have cool stories and useful pieces of advice to share, hence this blog. If you want to read about other things I do or get in touch, see my homepage.

Recent posts

Index of last names mentioned in posts

The pastor’s gardener and the importance of godparents

24 Sep 2025

I spent the last few weeks intensively researching the family of my newly identified second great-grandmother Emma Otīlija Driksone (born 1874 in Lazdonas mācītājmuiža). Her parents Juris Driksons (born 1849 in Patkule) and Ieva Lūkina (born 1838 in Jaunate) moved around a real lot, and I’m both proud of and suprised by how many sources on them I managed to find.Liberts Lūkins (born 1814 in Jaunate) of Mazsalaca parish was a teacher. He lived to the age of 77 and had at least nine children. Most of them stayed in the general area, that is, in the very north of Latvia close to the Estonian border. Two of his daughers, Ieva (born 1838) and Liene (born 1840), left the region in their twenties. Liene married Lībis Freijs (born 1840 in Jaunate), and they moved to Lazdona in the very southeast of Vidzeme close to Latgale. Ieva, still single at the time, followed them. We know this because Ieva was listed as one of the godparents or sponsors of Luīze Freija (born 1864 in Lazdonas mācītājmuiža), the first daughter of Liene and Lībis.Nine years later, Ieva married Juris Driksons, a local from Lazdona parish. At the time of their marriage, they were recorded as residing in or near a tavern called Slapje. Its building is still standing near Sarkaņi. One year later, when their first daughter Emma was born, Ieva and Juris lived by the pastorate of Lazdona parish. This is where Ieva’s sister Liene and her husband Lībis had been living for at least ten years by the time, as we know from their multiple children’s baptism records. Some of them also mention Lībis’s work as a gardener. Most remarkably, almost all of these records have pastor Rudolf Guleke (born 1831 in Mazsalaca) or his family members as godparents (sponsors).It’s probably not a coincidence that the Lazdona pastor of the time was born in Mazsalaca just like Lībis, his wife and her sister. It now seems very likely that pastor Rudolf Guleke hired Lībis as his gardener while still living in his original hometown, then was appointed to Lazdona and took Lībis and his family with him.Not all of Lībis and Liene’s children were born in Lazdona. At some point, they moved to Vecpiebalga, as that’s where their last son Artūrs Freijs was born in 1879. Guess what we know about pastor Rudolf Guleke? Vecpiebalga is where he died. It looks like Lībis’s gardening job was a lifelong commitment and he moved to wherever his priestly employer went.Finally, in 1897, we find Emma’s parents Juris and Ieva as well as Ieva’s sister and Lībis’s widow Liene and her children living together in Gostiņi, a majority-Jewish town in Latgale. If anything lasted longer than Lībis’s commitment to gardening, it was his wife’s friendship with her sister, that is, my third great-grandmother. Now that I know this, it’s Liene’s descendants that I enjoy researching more than those of Ieva’s other siblings. They somehow feel closer – after all, my second great-grandmother and Liene’s children grew up together.P. S. One of Emma’s children born in 1906 in Saint Petersburg had Catharine Lutz from Irši, a German colony in Latvia, as his godmother. Liene’s daughter Alma Emīlija Anna Freija (born 1874 in Lazdona) married Johann Carl Hauk, also an Irši native, when they all lived together in Gostiņi. I don’t yet know how to connect these facts, but it’s probably not a coincidence.

The Lūkins family and my unexpected connection to the massive genealogical tree of Mazsalaca

5 Sep 2025

All of the Latvian families mentioned in my previous posts, those my research has been focused on for the past three years, are my ancestors and relatives through my maternal grandmother Irina Pruss (Latvian spelling Prūse, born 1943 in Atyrau, Kazakhstan). I remember hearing in childhood that my grandfather, Irina’s ex-husband Pavel Minaev (born 1940 in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine) also had Latvian heritage. For a long time, I though it was impossible to find out how distant it was and where it came from.But eventually, long talks to my granddad and him looking for old photos in family albums gave me a name. A Latvian lady known as Emma Yurovna or Emma Yegorovna (the latter word being a Russian patronymic, not a last name) turned out to be Pavel’s paternal grandmother. In fact, granddad even remembered seeing her as a kid when she visited their Zaporizhzhia home with her husband also named Pavel Minaev (born around 1879 in Karelkino, Russia). I knew that Pavel and Emma’s son Valentin, my great-grandfather, was born in 1908 in Saint Petersburg. Since his father Pavel was an Orthodox Christian, Valentin’s birth record would’ve been in an Orthodox church book, and I had very little experience in locating those.I reached out to Ilya Yegorov, a friend who knows a lot about Russian genealogy. It took him just a few minutes to find the record but alas – unlike most Lutheran pastors in Latvia, Russian Orthodox priests didn’t write mothers’ maiden names in birth records. Ilya and I checked if there was a marriage record for Pavel and Emma at the same church. There wasn’t. At this point I thought we’d never find out where in Latvia Emma came from but Ilya didn’t give up. Having little luck with Saint Petersburg archives, he turned to Moscow, and there it was, Pavel and Emma’s marriage record from 1900 which contained her maiden name Driksone and her birthplace in Patkules pagasts.Being much more familiar with Latvian church records, it took me a couple minutes to locate her birth record. There she was, my newly found second great-grandmother Emma Otīlija Driksone (born 1874 in Lazdonas mācītājmuiža)! As I quickly found out, her father Juris Driksons (sometimes spelled Dristons, born 1849) came from Patkule where his ancestors lived for many generations. Her mother Ieva Lūkina (born 1838 in Jaunate), however, was from a different part of Vidzeme around Mazsalaca. Ieva’s father Liberts Lūkins (born 1814 in Jaunate) was a teacher at the nearby Košķele manor then known as Osthof – and a member of an incredibly huge and well-researched family.If you’re interested in Latvian genealogy, I’m sure you know Antra Celmins, the author of Discovering Latvian Roots. Well, turns out we’re related through the Lūkins family of Jaunate! Let me quote a post from her blog and you’ll understand why I’m so excited about this find.“The Lūkins family of the Mazsalaca area is absolutely massive, as I mentioned in Liberts’ post, and I haven’t had the opportunity to sort them all out myself – but thankfully, a lot of the work has been done for me. The Mazsalaca area has been very active in the gathering of genealogical data, both pre-Internet and in the Internet age. There is a “Family Tree Room” at the Mazsalaca district museum (that reminds me, I should get up there sometime this summer…) which contains trees compiled by a genealogist several decades ago. Now in the Internet age, the regional family tree is the largest Latvian tree on MyHeritage, and includes over 34,000 names. This is where I learned that I am distantly related by marriage to interwar Latvian president Kārlis Ulmanis. This family tree also helped me sort out my precise relationship to Augusts Kirhenšteins, the first leader of the Latvian SSR, after Latvia was occupied by the Soviet Union.”

Anna Priede’s mysterious husband: a Prussian Lithuanian side quest

2 Sep 2025

Thanks to a kind stranger from a genealogy forum, I managed to get a copy of my second great-grandfather’s personal file from one of his workplaces stored in a Saint Petersburg archive. The most interesting find it contained was his surprisingly detailed resume, practically an autobiography with lots of details unrelated to his work. The second great-grandfather in question is Jānis Ādams Voldemārs Prūsis (born 1875 in Viciebsk), also known as Johann Adam Woldemar Pruss, Joan Pruss and Vladimir Adolfovich Pruss depending on language and location.His mother Anna Elizabete Priede (born 1857 in Bieriņi) was born into the family of landowner and boatswain Kārlis Vilis Priede and Doroteja Elizabete Ozoliņa (born around 1831 and 1832 respectively, precise dates and locations yet unknown but likely within Rīga’s patrimonial district). She moved from Latvia to what now is Belarus and worked on the railroad. There, she met and married Heinrich Adolph Pruss (born 1848 in Skomenten), also a railroad worker, and became a housewife.A man named Heinrich Adolph Pruss surely was German, wasn’t he? Not according to my second great-grandfather! In his autobiography, he wrote, rather confusingly, “My father was of Lithuanian origin and my paternal grandma [i.e. his mother] was French.” What is the likelihood of someone being half Lithuanian and half French in the 19th century? Low for sure but not impossible considering Skomentnen, today Skomętno Wielkie near Ełk, Poland, belonged to East Prussia at the time. Lithuanians were indigenous to the broader region, and French people weren’t unheard of due to a number of Huguenot refugees settling in Prussia, at first around Berlin but then moving to various corners of the country for work or personal reasons.Still, the French part of the story sounded unconvincing, almost made up. A few Huguenot descendants in major cities like Königsberg is one thing, but one of them marrying a Lithuanian in a tiny village in the middle of nowhere? But I did find Heinrich Adolph Pruss’s birth record in the church books of Pissanitzen, the parish Skomenten belonged to. To my surprise, his parents were Carl Pruss (born 1818 in Schikorren) and Louise Gillet, the latter indeed being a French last name typical of Huguenots. Carl Pruss was the village teacher of Skomentnen and a co-founder of an insurance company named Masowia.Now, something else felt unconvincing. While there were Lithuanians in East Prussia, they generally lived in a different part of it. The district Skomentnen and Schikorren belonged to was overwhelmingly ethnically Polish with a German minority in urban areas. As few as 6 residents out of almost 30,000 were Lithuanian according to a local census from the 1840s. The closest area with at least a couple majority-Lithuanian villages was Goldap some 50 kilometers to the north. Even there, they were rapidly assimilating into Germans. The few who maintained a Lithuanian identity typically had remarkably different names and were ordinary peasants unlikely to teach or found companies.Perhaps Carl Pruss’s parents moved to Schikorren from a more Lithuanian area and Germanized their last name? Church records don’t support this theory. His father born in the 1790s had an even more German first name Gottlieb and the same last name Pruss. His birthplace isn’t known but there are records of him living in Schikorren well before his son Carl’s birth. Moreover, Carl’s mother Catharine Erdt came from a village even farther to the south and was half German and half Polish.Where’s the Lithuanian? I don’t have a clear answer to this day. Is it possible that it’s Gottlieb Pruss’s parents who lived somewhere else, were Lithuanian, became Germanized way earlier than most Prussian Lithuanians and yet somehow transmitted memories of their Lithuanian origin to their great-grandson despite two generations of intermarriage with non-Lithuanians between them? Possible, yes. Likely? Not really.Since there’s no paper trail to prove or disprove this, I can only rely on what my second great-grandfather wrote. In addition to his father’s supposed Lithuanian origin, Jānis Ādams Voldemārs Prūsis mentioned that he himself grew up speaking German and “never learned Lithuanian and Latvian.” From other sources we know for sure that Latvian was his mother’s first language and that some of his siblings spoke it well and identified as Latvians first and foremost (one was even murdered for this by the NKVD but that’s a different story).So, Latvian was actually present in his household growing up, even if he never mastered it. His mention of Lithuanian in the very same context suggests that he saw at least a theoretical opportunity to learn it, perhaps from his father or grandfather. Maybe they did speak it after all?

From gendarmerie to sidewalk astronomy: a new source on the Morr family from Rīga

31 Aug 2025

The earliest ancestor I knew from my grandma’s stories before I started archival research was my third great-grandfather Jacob Morr (born 1840 in Rīga). I knew he studied in Tartu, worked as a teacher on Saaremaa, married the daughter of an Estonian merchant and finally moved to Saint Petersburg where he headed a prestigious school. As I later learned from church records, Jacob’s father Georg Gottfried Morr (born 1815 in Rīga) was a government official, son of a German immigrant from East Prussia. Jacob’s mother Anna Dorothea Löwenthal (born 1811 in Voleri) came from a Latvian family with a complex history of name changes. Her father was a maritime pilot named Miķelis Sproģis (born 1787 in Kundziņsala), yet she claimed her maiden name was Löwenthal like her mother’s. To make it more confusing, the mother in question, Maria Theresia Löwenthal (born 1789 in Liepāja), got this last name only because her father Johann Salomo Wischkewitz (born 1759, possibly in Gramzda), a Latvian, picked a German name to sound more fancy.But let’s get back to the Morrs. I’ve had lots of data on Jacob Morr’s life story and all of his descendants for a while. What I didn’t know until just yesterday was what happened to his numerous siblings. Surprisingly, it was a book by the Russian poet Igor Chinnov (born 1909 in Tukums) that shed light on this. Igor’s paternal grandmother Wilhelmine Maria Morr (born 1850 in Rīga) turned out to be a sister of Jacob Morr. Growing up in Latvia and visiting Estonia, Igor Chinnov met many members of the extended Morr family and described them in his memoir. Among other things, he mentions two of his Morr cousins working as top managers at the Rīga branch of an insurance company called Salamandra and owning a large building in Grīziņkalns.He also mentions Alexander Morr (born 1878 in Odesa), son of Jacob Morr’s brother Friedrich Robert Morr (born 1844 in Rīga) and Ekatharina Aphanassiewa. Alexander was a gendarmerie colonel in the late 1910s, described as a staunch monarchist loyal to the Russian Empire and eager to suppress protests against it. Unsurprisingly, he lost his job after the revolution and Latvia’s independence. According to Igor Chinnov’s memoir, he then bought a telescope and earned a living standing next to the Freedom Monument in Rīga and offering passers-by to take a look at the stars for a small fee.Chinnov recalls an argument between Alexander Morr and his wife Natalie Orechowa where the latter exclaimed proudly, “My father is a Russian officer, not some Reval sprat like yours.” While humorous, this episode is socially insightful. First, this joke wouldn’t make sense without a pre-existing context of ethnic Russian supremacism and xenophobic attitudes towards Latvians and Baltic Germans. Secondly, Reval is the old name of Tallinn, a city the Morrs had nothing to do with, adding yet another xenophobic subtext of “Latvians, Estonians, whatever, they’re all the same thing.”

Why would a Kurzeme peasant change his name twice?

26 Aug 2025

There lived a man in Liepāja in the 18th century, a direct ancestor of mine, named Johann Salomo Wischkewitz. Or Wiskiewitz. Or Wistkewitz. Or even Bietzkewitz! Local pastors were remarkably unsure how to spell his last name. This may have contributed to his decision to change it, although it surely wasn’t the only reason. The few things we know about Johann Salomo are his work as a Stadtsoldat (basically a municipal police officer), his marriage to a Latvian lady named Magdalena Sehn (Zēna in modern spelling) and the fact that he chose to be called Löwenthal at an early point in his life.What we don’t know is where he came from. Judging by the age on his death record, he was born around 1759. Liepāja was still a small town at the time, but a rapidly growing one as it was one of just two sea ports in the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Combined with its location near the Prussian border, political ties to Poland and Lithuania and economic ones to the Russian Empire, this rapid growth meant so much immigration that most Liepāja residents were born not in Liepāja but elsewhere.Was Johann Salomo one of the immigrants, perhaps a Germanized Pole or a Prussian Lithuanian? It remains a possibility but it seems much more likely that he was a Latvian, a Kurzeme native who moved to the city from a nearby village. The few Prussian locations where last names similar to Wischkewitz were common are quite far away from the border with Courland. At the same time, the last name Venškēvics and various versions thereof were commonly found among Latvian peasants in the parish books of Gramzda and Bārta, both currently part of the South Kurzeme municipality which surrounds Liepāja.Four more pieces of indirect evidence support the Gramzda theory of Johann Salomo’s origin. First, another Johann Wischkewitz from Gramzda worked as a Kammerdiener for one of the Couronian dukes, suggesting that this rural Latvian family was no stranger to working for the government which was not that typical for peasants. It is then no wonder that his possible relative became a Stadtsoldat. Secondly, Johann Salomo’s wife’s relatively uncommon maiden name Zēna is also found in Gramzda, suggesting that they may have moved from there to Liepāja together. Thirdly, like I’ve already mentioned, Johann Salomo changed his last name to Löwenthal. Church records from Gramzda mention a German resident named Reinhold Löwenthal, again a rather uncommon last name in Latvia, and this may mean that Johann Salomo took the name from his neighbors. According to Bruno Martuzāns, it was not unusual for Latvians to borrow German names like that. Lastly, another Löwenthal who lived in Liepāja in the early 19th century and likely was Johann Salomo’s son was outright described as ein Lette (a Latvian) in his marriage record.Johann Salomo’s own marriage record and most of his children’s birth records read Wischkewitz genannt Löwenthal, genannt being German for “named” or “known as.” The children themselves used only one last name later in life, the new one. We already know where Johann Salomo’s new last name may have come from, but why did he change it at all? Well, Germans dominated urban areas in most of Latvia at the time, and even more so in Courland. German was the prestigious language of city life, education and social mobility. Picking a fancy-sounding German name was both a proof of social standing (not everyone would’ve been allowed to change their name legally) and a way to further increase one’s status.Johann Salomo Wischkewitz genannt Löwenthal’s descendants continued the trend. His daughter Maria Theresia Löwenthal (born 1789 in Liepāja) moved to the Daugavgrīva parish near Rīga and married a Latvian maritime pilot from Kundziņsala named Miķelis Sproģis. When their eldest daughter Anna Dorothea (born 1811 in Voleri) moved to Rīga proper and married a German man, she told the pastor her maiden name was Löwenthal, not Sproģe as one’d expect. Normally, you get your last name from your father, not mother. But if your father’s name is “peasantly” Latvian and your mother’s “fancily” German, it looks like an exception can be made.Anna Dorothea’s son Jacob Morr (born 1840 in Rīga) eventually moved to Tartu for university and then to Saint Petersburg for work as the headmaster of a prestigious school. It seems like he didn’t preserve his mother’s Latvian identity and felt completely German. However, his daughter Charlotte Wilhelmine Johanna Morr (born 1885 in Tartu), my second great-grandmother, married another Latvian, my second great-grandfather Voldemārs Prūsis. It’s through him that I am connected to Teodors Prūsis who was murdered by the Soviets as an alleged Latvian spy and to Ādams Priede, president of the community court of Bieriņi in the 1840s, but let’s leave that for another post.P.S. Several individuals from Gramzda were recorded at different points in time as changing their last name from Wisgausche (modern spelling Visgaušs) to Wischkewitz or using both at once, suggesting that the two last names were somehow perceived as versions of each other. I can’t prove this yet, but it’s possible that Johann Salomo was originally a Wisgausche and changed his name twice, first from that to Wischkewitz and then from Wischkewitz to Löwenthal. This suggests an obvious hierarchy: Latvian names as the least cool, Polish-like ones as a bit cooler and German ones as the most respected. Seems pretty close to the reality of the 18th century. Thankfully, not the case anymore as Latvia is free from all colonizers and proud of its language.

Useful resources and tips for Latvian genealogy

24 Aug 2025

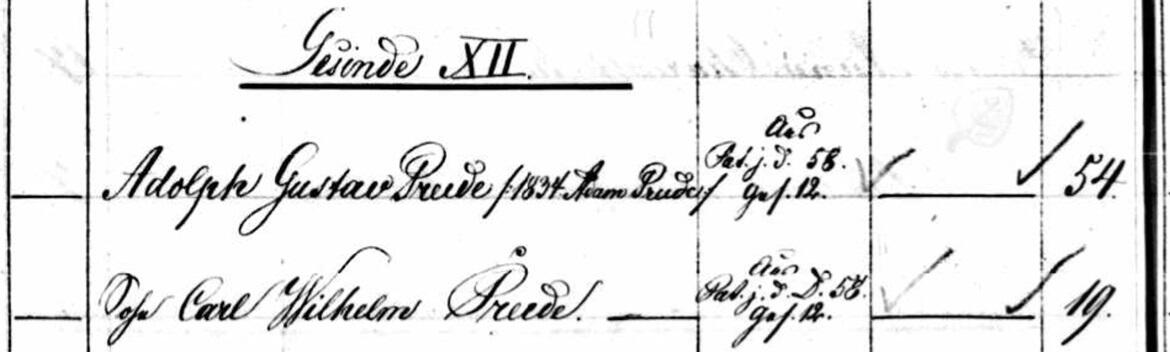

If you want to find out about your Latvian ancestors, Raduraksti is the website you’ll need the most by far. Run by the Latvian State Historical Archive, it requires signing up but is completely free to use. The interface is in Latvian only but it’s Google Translate’able and easy to get used to. The three collections you are most likely to consult are baznīcu grāmatas, church records of births, confirmations, marriages and deaths; dvēseļu revīzijas, local censuses conducted by Russian Empire officials, and Latvijas iedzīvotāju pases, a database of passports issued to Latvian citizens between 1918 and 1940.The baznīcu grāmatas collection is sorted by denomination first and parish second. If the people you’re looking for were ethnic Latvians, you’ll most likely find them under the luterāņi section and sometimes under baptisti, unless they lived in Latgale or near Alsunga where most were Catholic, in which case you should go for Romas katoļi. Baltic Germans were usually luterāņi and sometimes reformāti. Keep in mind that the line between Latvians and Baltic Germans is quite blurry, one could become the other due to upwards social mobility. Russians are either pareizticīgie or vecticībnieki and Jews are Mozus ticīgie.Once you choose the right denomination, you will see a list of draudzes or parishes. The Lutheran ones have two names, one in Latvian and one in German. Historic parishes don’t always coincide with Latvia’s modern-day administrative divisions. If you know the name of the village your ancestors lived in, check the pagasts it currently belongs to. Then you’ll need another useful resource, Ciltskoki, to find out what parish it belonged to. To make sure you don’t get lost between the frequent and confusing border changes, you can find maps of each parish and lists of estates in them by adding draudzes novads (parish district) to the name and looking that up on Latvian Wikipedia. For example, many of my ancestors lived in Daugavgrīvas draudzes novads, and their records can be found in Raduraksti’s Daugavgrīvas (Dünamünde) section. Once you find the right parish, you’ll see a list of church books with year ranges and letter codes that correspond to types of recorded events such as baptism, confirmation, marriage or burial. Some parishes have separate books for latviešu (Latvian) and vācu (German) residents, others don’t. Either way, from this point you just scan through the books hoping to find the names you’re looking for.Ciltskoki has many other useful pages such as a list of historic German place names in Latvia and their Latvian equivalents. It also has searchable databases of manually transcribed records from various archival sources including many of those available on Raduraksti. Some databases are free, while others need to be paid for with a text message sent from a Latvian phone number.Alternatively, you can search for individuals on Ancestry which has virtually all of Raduraksti’s church records and local censuses, again in a searchable form, although way less organized than Ciltskoki’s. It’s also a paid service but you can get a free trial, check whatever you want and cancel it within two weeks without paying anything. If you go this way, open the Search tab, choose All Collections, then open the Card Catalog on the right and find the Latvia section. The two collections you’re most likely to find useful are called Latvia Births, Marriages and Deaths, 1854-1939 and Latvia Census and Resident Registers, 1854-1897. Ignore the years, they are completely wrong. Let’s just say I’ve seen tons of records from the 1700s in the former.Ancestry treats each person mentioned in a transcribed church record (a newborn, a parent, a groom, a bride or a deceased) as a separate piece of data. That is, if there is a single record of a Karl Wilhelm Preede born into the family of Adam Preede and Dorothea Lisette Preede geb. Kungel, each of the three gets a card you can find via Ancestry’s search function. In theory, Ancestry extracts not just names but dates, types of events and locations. In reality, these fields are very often left empty by the system even when this information is given in the actual church book, so it’s best to not limit your query with any additional parameters and stick to just names. If you find the right record this way, you’ll get to see a scan of the original record with all the details.If you see too many people with the same full name and aren’t sure which one is yours, location may help narrow it down. Even if the cards don’t show any locations, you can still find it manually for each of them. First, you need to open the church book scan attached to the card. Then, find the handwritten page number in the corner and go back for as many pages as needed to get to page one. Go back a couple more pages before page one and you’ll likely find a white label added by the archive which says what parish the book is from.You may have noticed the spelling of the names in the example I gave is different from modern Latvian. The individual recorded as Adam Preede, an actual ancestor of mine, would be Ādams Priede if he lived today and not 150 years ago. In fact, fellow Latvians would call him Ādams Priede back then too, it’s just that most church books were written in German or a heavily Germanized version of Latvian. It wasn’t all that standardized, many other people named Ādams were recorded as Ahdam and not Adam. Thankfully, Ancestry’s search module isn’t that bad at guessing alternative name spellings. Still, it’s better to try all the likely options manually to make sure it doesn’t miss anything. It’s worth trying to add h after long vowels, use sch for š and tsch for č and drop the s in the end.